- Home

- Roméo Dallaire

Shake Hands With the Devil

Shake Hands With the Devil Read online

CONTENTS

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

Maps

Introduction

1. My Father Told Me Three Things

2. “Rwanda, that’s in Africa isn’t it?”

3. “Check out Rwanda and you’re in charge”

4. Enemies Holding Hands

5. The Clock Is Ticking

6. The First Milestones

7. The Shadow Force

8. Assassination and Ambush

9. Easter Without a Resurrection of Hope

10. An Explosion at Kigali Airport

11. To Go or To Stay?

12. Lack of Resolution

13. Accountants of the Slaughter

14. The Turquoise Invasion

15. Too Much, Too Late

Conclusion

Glossary of Names, Places and Terms

Recommended Reading

Index

Copyright

About the Book

When Lt. General Roméo Dallaire received the call to serve as force commander of the UN mission to Rwanda, he thought he was heading off to Africa to help two warring parties achieve a peace both sides wanted. Instead, he and members of his small international force were caught up in a vortex of civil war and genocide. Dallaire left Rwanda a broken man, disillusioned, suicidal, and determined to tell his story.

An award-winning international sensation, Shake Hands with the Devil is a landmark contribution to the literature of war: a remarkable tale of a soldier’s courage and an unforgettable parable of good and evil. It is also a stinging indictment of the petty bureaucrats who refused to give Dallaire the men and the operational freedom he needed to stop the killing. ‘I know there is a God,’ Dallaire writes, ‘because in Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him and I have touched him. I know the devil exists and therefore I know there is a God.’

About the Author

Lt. General Roméo Dallaire served as force commander of the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda from July 1993 to September 1994. Shake Hands with the Devil, his eyewitness account of the Rwandan genocide, won the Shaughnessy Cohen Award and the Governor General Award.

Shake Hands with the Devil

The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda

Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire

with Major Brent Beardsley

To my family and the families of all those who served with me in Rwanda, with deepest gratitude

Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called the children of God.

Matthew 5:9

To the Rwandans, abandoned to their fate, who were slaughtered in the hundreds of thousands

To the fifteen UN soldiers under my command who died bravely in the service of peace and humanity

To Sian Cansfield, researcher, journalist and dear friend, who died on June 1, 2002, while working so hard to tell this story

PREFACE

This book is long overdue, and I sincerely regret that I did not write it earlier. When I returned from Rwanda in September 1994, friends, colleagues and family members encouraged me to write about the mission while it was still fresh in my mind. Books were beginning to hit the shelves, claiming to tell the whole story of what happened in Rwanda. They did not. While well-researched and fairly accurate, none of them seemed to get the story right. I was able to assist many of the authors, but there always seemed to be something lacking in the final product. The sounds, smells, depredations, the scenes of inhuman acts were largely absent. Yet I could not step into the void and write the missing account; for years I was too sick, disgusted, horrified and fearful, and I made excuses for not taking up the task.

Camouflage was the order of the day and I became an expert. Week upon week, I accepted every invitation to speak on the subject; procrastination didn’t help me escape but pulled me deeper into the maze of feelings and memories of the genocide. Then the formal processes began. The Belgian army decided to court-martial Colonel Luc Marchal, one of my closest colleagues in Rwanda. His country was looking for someone to blame for the loss of ten Belgian soldiers, killed on duty within the first hours of the war. Luc’s superiors were willing to sacrifice one of their own, a courageous soldier, in order to get to me. The Belgian government had decided I was either the real culprit or at least an accomplice in the deaths of its peacekeepers. A report from the Belgian senate reinforced the idea that I never should have permitted its soldiers to be put in a position where they had to defend themselves—despite our moral responsibility to the Rwandans and the mission. For a time, I became the convenient scapegoat for all that had gone wrong in Rwanda.

I used work as an anodyne for the blame that was coming my way and to assuage my own guilt about the failures of the mission. Whether I was restructuring the army, commanding 1 Canadian Division or Land Force Quebec Area, developing the quality of life program for the Canadian Forces or working to reform the officer corps, I accepted all tasks and worked hard and foolishly. So hard and so foolishly that in September 1998, four years after I had gotten home, my mind and my body decided to give up. The final straw was my trip back to Africa earlier that year to testify at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The memories, the smells and the sense of evil returned with a vengeance. Within a year and a half, I was given a medical discharge from the army. I was suffering, like so many of the soldiers who had served with me in Rwanda, from an injury called post-traumatic stress disorder. With retirement came the time and the opportunity to think, speak and possibly even write. I warmed to the idea of a book, but I still procrastinated.

Since my return from Rwanda in 1994, I had kept in close touch with Major Brent Beardsley, who had served as the first member of my mission and had been with me from the summer of 1993 until he was medically evacuated from Kigali on the last day of April 1994. Brent used every opportunity to press me to write the book. He finally persuaded me that if I did not put my story on paper, our children and our grandchildren would never really know about our role in and our passage through the Rwandan catastrophe. How would they know what we did and, especially, why we did it? Who were the others involved and what did they do or not do? He said we also had an obligation to future soldiers in similar situations, who might find even a tidbit from our experience valuable to the accomplishment of their missions. Brent collaborated at every stage in the writing of this book. I thank him for his prompting and his support. I am also grateful to his wife, Margaret, and his children, Jessica, Joshua and Jackson, for loaning him to me through the initial research and drafting, through the reviews and most recently for his work to help me finish the manuscript. Brent was the catalyst, the disciplinarian and the most prolific scribe; he committed day after day to the work in order that I could complete this project. Even in periods of enormous suffering from the debilitating effects of overwork, lack of sleep and his own affliction with post-traumatic stress disorder, Brent always went well beyond the effort required of him. He has become my soulmate for all things Rwandan; he provides the sober second thought and voice to my efforts surrounding the Rwandan debacle. His willingness to be a witness for the prosecution at the never-ending International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and his support for my own involvement have cemented our lives together in the best tradition of ex-warriors returning from the front. He has saved me from myself, and I owe my life, as well as the guts of this book, in part to him.

I am especially grateful to Random House Canada for taking a chance on a non-author and a sick veteran. I am grateful for their understanding, their encouragement and their support. A very special thanks goes to my editor and friend, Anne Coll

ins. Without her advice, encouragement and discipline, this project might not have been completed. She kept telling me that this book must be written and that it would be written. For many months I did not put in the effort required, but she held firm, showed genuine concern for me and proved to be the most patient person of us all. She is a lady who takes risks, and I admire her courage and determination. I also wish to thank my agent, Bruce Westwood, for his belief that somewhere in me, we would find the man who could write this story. He kept a friendly eye on me and encouraged me every step of the way. He has become a close colleague, and I respect his skills and experience in the complex world of publishing.

I assembled an ad hoc staff for this project, who worked together magnificently in mutual respect and co-operation. Major James McKay, a long-time researcher for my efforts with the tribunal and on matters of conflict resolution, was my “futures” person. I thank him for his support. Lieutenant Commander Françine Allard, a dogged researcher and “keeper of the documents,” worked for me while I was still serving in the Canadian Forces. Fluent and articulate in six languages, she was committed to this book and a cherished member of the team. A special thanks must also go to Major (Retired) Phil Lancaster, who replaced Brent in Rwanda as my military assistant during my final months in the mission area. He helped me draft the chapters on the war and the genocide. A soldier, doctor of philosophy, and a compassionate humanitarian, Phil has worked with war-affected children in the Great Lakes region of Africa almost full-time since his retirement. He has never really returned from Rwanda, and I admire him and the work he does.

Dr. Serge Bernier, the Director of History and Heritage at the Canadian National Defence Headquarters and a classmate of mine from cadet days, provided very personal encouragement and constant contact throughout the project. He reviewed the French version and also provided resources and support for the official history of the mission as debriefed by me to Dr. Jacques Castonguay. He remains a voice of stability in my life.

In addition, there were many extended family members, friends, colleagues and even strangers who encouraged me throughout the writing of this book. I needed that often very timely encouragement and I will be eternally grateful.

In Rwanda today there are millions of people who still ask why the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), the United Nations (UN) and the international community allowed this disaster to happen. I do not have all the answers or even most of them. What I do have to offer the survivors and Rwanda’s future generations is my story as best as I can remember it. I kept daily notes of my activities, meetings, comments and musings, but there were many days, particularly in the early stages of the genocide, when I did not have the time, the will or the heart to record the details. This account is my best recollection of events as I saw them. I have checked my memory against the written record as it survives, in code cables, UN documents and my papers, which were released to me by the Canadian Forces. If there are any errors in the spelling of the names of places or persons, or misremembered dates, I offer my apologies to the reader. I remain fully responsible and accountable for every decision and action I took as the sometime Head of Mission and full-time Force Commander of UNAMIR.

My wife, Elizabeth, has given more than I can ever repay. Beth, thank you for the days, weeks, months and years when I was absent and you held the home front and the family together, whether I was off serving around the world, at home in my workaholic bubble, or just out in the back forty on exercise, waking you and everyone else in the married quarters with the sound of our guns. Thank you for your support during this last duty, which has been one of the hardest and most complex efforts of my life. I thank my children, Willem, Catherine and Guy, who grew up without a full-time dad but who have always been the pride of my life, the true test of my mettle, and who continue to make their own place in the world. Be yourselves and thank your mother. One of the reasons I wrote this book was for you, my very close family, so that in these pages you may find some solace for the toll my experience in Rwanda has exacted, and continues to exact, from you—far beyond the call of duty or “for better or for worse.” I am not the man who left for Africa ten years ago, but you all stayed devoted to this old soldier, even when you were abandoned by the military and the military community in the darkest hours of the genocide. You saw first-hand what happens to the spouses and families of peacekeepers. I remain forever thankful that you so clearly opened my eyes to the plight of the families of a new generation of veterans. You are the ones who really started the Canadian Forces Quality of Life Initiative.

I have dedicated this book to four different groups of people. First and foremost, I have dedicated it to the 800,000 Rwandans who died and the millions of others who were injured, displaced or made refugees in the genocide. I pray that this book will add to the growing wealth of information that will expose and help eradicate genocide in the twenty-first century. May this book help inspire people around the globe to rise above national interest and self-interest to recognize humanity for what it really is: a panoply of human beings who, in their essence, are the same.

This book is also dedicated to the fourteen soldiers who died under my command in the service of peace in Rwanda. The hardest demand on a commander is to send men on tasks that may take their lives, and then the next day to send others to face possibly similar fates. Losing a soldier is also the hardest memory to live with. Such decisions and actions are the ultimate responsibility of command. To the families of those courageous, gallant and devoted soldiers I offer this book to explain. When the rest of the world failed to even offer hope, your loved ones served with honour, dignity and loyalty, and paid for their service with their lives.

This book is also dedicated to Sian Cansfield. Sian was this book’s shadow author, but she did not live to see it finished. For almost two years, she immersed herself in everything Rwandan. Her uncanny memory was a researcher’s gift. I enjoyed her sparkle, her enthusiasm, her love of Rwanda and its people, whom she came to know in the field a few years after the war. Her journalistic aggressiveness to get at the truth combined with her energy and her zeal to evoke the heart of the story earned her the title of “regimental sergeant major” of our team. We worked well together and enjoyed many laughs and too many tears as I recounted hundreds of incidents and experiences, tragic, revolting, sickening and painful. In the last stages of the drafting of the book, I noticed she was tiring as the content and the workload ate away at her sense of humour and objectivity. I sent her on leave for a long weekend to rest, sleep, eat and recharge her batteries, as I have done so often with officers or soldiers who showed the same symptoms. The morning after she left for the weekend, a phone call broke the news to me that she had committed suicide. Sian’s death hit me with a pain I had not felt since Rwanda. It seemed to me that the UNAMIR mission was still killing innocent people. The following week, I joined her family in attending her funeral and mourned her passing. The sense of finality and the shock that came from her death brought to life the spirits that have been haunting me since 1994. I wanted to cancel the project and let my tale die with me. Encouraged by her family and my own, especially Beth, by the rest of the team and many friends, I came to realize that the best tribute I could pay to Sian was to finish the book and tell the story of how the world abandoned millions of Rwandans and its small peacekeeping force. Sian, so much of this book is dedicated to you; your spirit lives with me as if you were another veteran of Rwanda. May you now find the peace in death that so eluded you in life.

The fourth group to whom this book is dedicated comprises the families of those who serve the nation at home and in far-off lands. There is nothing normal about being the spouse or child of a soldier, sailor or airperson in the Canadian Forces. There are very good and exciting times and there are also hard and demanding times. In the past, this way of life was very rich and worthwhile. But since the end of the Cold War, the nature, tempo and complexity of the missions on which our government has sent members of the C

anadian Forces have caused a significant toll in marriage casualties. The demands of single parenthood, loneliness and fatigue, and the visual and audio impact of twenty-four-hour news reporting from the zones of conflict where loved ones have been sent create stress levels in the families of our peacekeepers that simply go off the chart. Our families live the missions with us, and they suffer similar traumas, before, during and after. Our families are inextricably linked to our missions, and they must be supported accordingly. Until the last few years, the quality of life of our members and their families was woefully inadequate. It took nearly nine years of hurt all round before the government began to accept its responsibilities in this regard. Witnessing the deep emotion and genuine empathy of Canadians for our soldiers who were wounded or killed in Afghanistan, I am optimistic that the nation as a whole will finally and fully accept its responsibility for these young and loyal veterans and their families. I pray that this book will assist Canadians in understanding the duty they and the nation owe to the soldiers who serve us, and to their families.

The following is my story of what happened in Rwanda in 1994. It’s a story of betrayal, failure, naïveté, indifference, hatred, genocide, war, inhumanity and evil. Although strong relationships were built and moral, ethical and courageous behaviour was often displayed, they were overshadowed by one of the fastest, most efficient, most evident genocides in recent history. In just one hundred days over 800,000 innocent Rwandan men, women and children were brutally murdered while the developed world, impassive and apparently unperturbed, sat back and watched the unfolding apocalypse or simply changed channels. Almost fifty years to the day that my father and father-in-law helped to liberate Europe—when the extermination camps were uncovered and when, in one voice, humanity said, “Never again”—we once again sat back and permitted this unspeakable horror to occur. We could not find the political will nor the resources to stop it. Since then, much has been written, discussed, debated, argued and filmed on the subject of Rwanda, yet it is my feeling that this recent catastrophe is being forgotten and its lessons submerged in ignorance and apathy. The genocide in Rwanda was a failure of humanity that could easily happen again.

Shake Hands With the Devil

Shake Hands With the Devil Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda

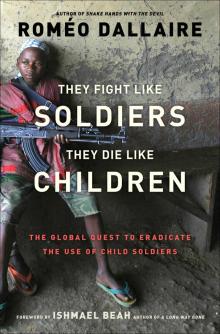

Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children

They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children